The future of coal-fired power will be written in Asia — regardless of what Europe thinks.

Not only can steam be superheated — so can political debates. Coal-fired power plants have long been in the crosshairs, and politically their future may seem settled, yet economically and technically the match is far from over. The harmful impacts of burning coal — such as high carbon dioxide emissions and environmental pollution — are well known. As a result, there is a strong global push to find viable solutions, while ‘shut it down, period’ political decisions can quickly win a few percentage points in an election.

And again, the ugly truth: the future of coal-fired power will be written in Asia — regardless of what Europe thinks. Energy hunger and challenges are local. What options do India and China have? Let’s move the question into the technical domain and explore the present and future of coal power in this newly launched, multi-part series. In the introduction, I’ll lay out the expected trends and frame the topic as thoroughly as possible — and I’m confident we’ll see many things differently.

I want to make one thing clear upfront: I’m looking at this topic from a technical angle, for educational purposes. My core thesis is that facts speak and numbers scream — without narratives or ‘isms’. I’m not a member of any organization, just a regular dude from the oil & gas 🙂

We demand that they shut them down immediately!

Seriously. On Friday afternoons, young people in Western Europe march on the streets and demand an immediate shutdown for coal-fired power plants — and they’re met with deaf ears. Why don’t we just shut them down? That’s a serious question…

Because, physically, we can’t replace them right now. To understand what this is really about, let’s look at Figure 1. Primary energy consumption in Europe, North America, and Oceania (Australia and the surrounding region) is stagnating. Central and South America are starting to grow from a low base — hand in hand with Africa — while Asia is growing like crazy. Asia alone consumes more energy than all the other continents combined + a 20,000 TWh backpack. For decades, Asian consumption was driven by China, but India will likely add several thousand TWh in the future.

Of course, the obvious question is: what is this energy demand being met with? This is where our main character comes in — coal. In Figure 2, coal’s share remains above 40% and, at first glance, shows a declining trend. At this point, politics can straighten its tie and collect the praise, but now comes the ugly truth again. In reality, the situation isn’t improving — on the contrary, it’s getting worse. To comprehend the situation, you have to read these two charts together. If primary energy consumption is rising steeply, then a slightly declining — and in fact essentially flat since 2015 — coal share still translates into a substantial absolute increase. Ouch.

This already makes the story look completely different — and it shows how detached from reality the ‘we demand that they shut them down immediately’ slogans really are. But the truly shocking trend is shown in Figure 3, which displays coal consumption. Asia’s coal consumption is growing at an astronomical rate — and it has effectively wiped out Europe’s efforts in less than ten years. The divergence has only widened over time, despite all the climate summits and multilateral agreements that have taken place in the meantime.

And finally, let’s take an even closer look at what the situation is like specifically in India and China. Figure 4 makes it clear: if we’re talking about the future of coal-fired power, these are the two countries we need to focus on.

In the chart, I included changes in coal consumption and primary energy consumption. In China’s case, there was an extremely strong surge; in India, growth is clearly visible as well — from 1995 to 2015, primary energy consumption doubled. Although India has now become the world’s most populous country, its per capita energy consumption still lags far behind China’s. Superpower ambitions also require an industrial base to match — and that requires energy. A LOT…

In India’s case, there is the pledge to rely on renewables for 50% of its energy — but let’s not forget we’re talking about future demand on the order of many tens of thousands of TWh. We should also mention the nuclear programs, the serious technical participation in international projects aimed at developing fusion reactors, and the ramping investments in wind, solar, and hydropower. But a 50–50 split between fossil and renewable sources in a country the size of a continent would still translate into massive CO₂ emissions.

Coal remains the energy source that can be extracted most easily and in the largest quantities, with enormous reserves in many parts of the world. In 2024, annual coal production was 9.1 billion tonnes, and if we take the roughly 1,050 billion tonnes of proven reserves into account, then even at today’s production rate the reserves would last on the order of 100–110 years. That’s the one trillion question, how — or in what way — we choose to utilize this energy.

And there was light — and there were problems, too

After the global context, let’s move on to the technical thread introduction. Coal-based power plants have been with us for nearly 200 years, continuously evolving. At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, humanity faced a new problem for the first time: there wasn’t enough energy. More and more steam was needed to drive more and more machines. That challenge acted as a catalyst for the development of engineering and the natural sciences, and many intellectual giants of the era worked on solutions. Building on increasingly deep mathematical and thermodynamic knowledge, ever better boilers were developed — operating at ever higher temperatures and pressures.

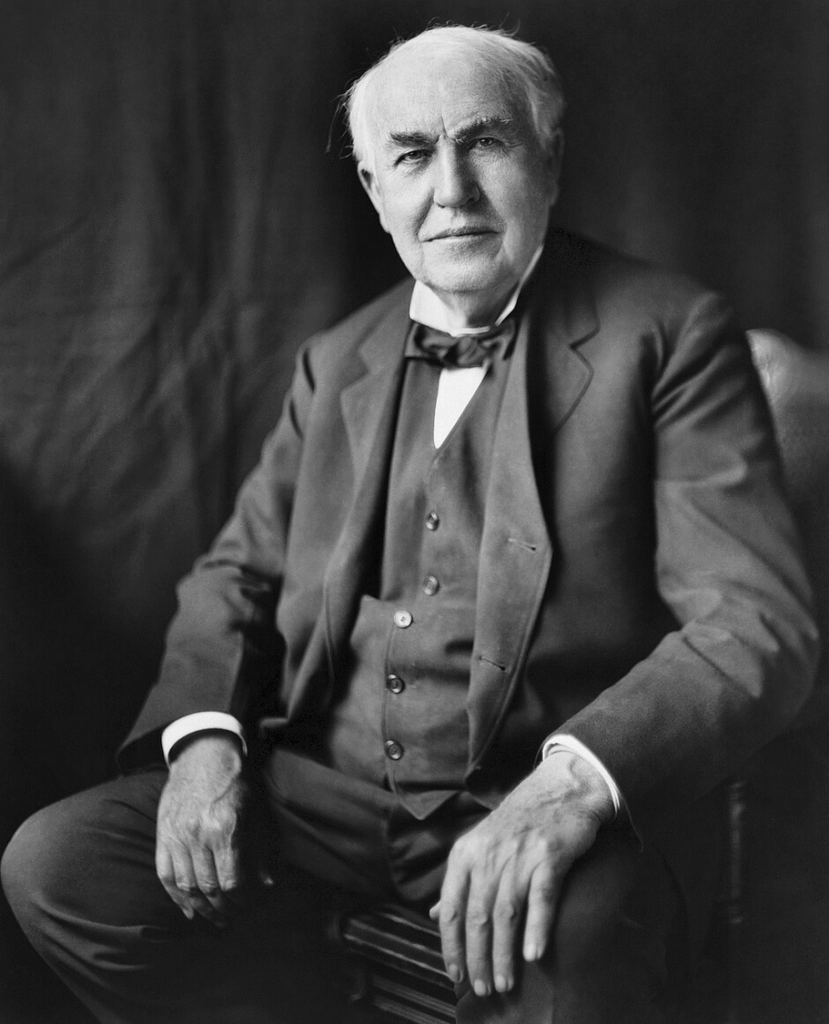

In January 1882 — almost three years after the invention of the incandescent light bulb — the world’s first coal-fired power station was inaugurated at 57 Holborn Viaduct in central London. The heart of the plant was a 93 kW generator designed by Thomas Edison, driven by the station’s steam engine. The generator’s 110 V direct current initially supplied 968 outdoor incandescent lamps, later expanded to 3,000. A year later, the centre of Milan was flooded with light.

The London power station was soon followed by several others around the world. The first American power station opened later that same year, on September 4, at 255–257 Pearl Street in Manhattan’s business district — also based on Edison’s designs. With six 100 kW steam dynamos, the Pearl Street Station was serving 508 individual customers and 10,164 incandescent lamps by 1884. The sequence continued with Berlin in 1885, and then Rome in 1886.

Edison vs. Tesla

If we look closely, by this period power-plant technology already had industrially mature technical solutions. But there was still a problem…

One of these was the question of how to transmit electric power — which culminated in the well-known clash between direct current (Edison) and alternating current (Tesla) around 1885–1886. By then, the transformer — thanks to the discoveries of Hungarian engineers — coupled with the already existing AC systems, clearly demonstrated the path forward. In the end, alternating current prevailed. But as it usually happens, a new problem surfaced…

Demand for electricity was enormous; the world was standing on the threshold of yet another industrial revolution. New inventions, new discoveries — but everything needed electric power, and that power had to be transmitted ever farther. Many players entered the market, yet there was no market regulation: everyone built whatever generator they wanted. Combined with the fact that the rotational speed of piston steam engines was not standardized either, this led to a situation where the frequency of the electrical supply became something that was essentially characteristic of a given power station. This brought two serious issues to the surface:

- The lower the AC frequency, the more annoying the flicker of incandescent lamps ⟶ we need to increase the frequency

- The higher the AC frequency, the greater the iron losses in transformers and electrical machines ⟶ we need to reduce the frequency

The optimum was eventually standardized at 50 and 60 Hz. Problem solved — we can lean back. As expected, another challenge appeared. The synchronous speed of a generator depends on the number of pole pairs, and it can be described by a very simple formula:

If we have only two pole pairs and , then the synchronous speed is 3,000 rpm; if we have four pole pairs, it’s 1,500 rpm. At first glance, this doesn’t seem like a big deal — but mechanically it’s a huge problem. The more pole pairs you have, the more complex and expensive the generator becomes, so the investment is slow and costly — but the driving steam engine can run at a lower speed. Or you use fewer pole pairs, which means a simpler generator, but then the steam engine has to operate at a higher rotational speed.

It runs rough and chugs – it’ not that cool

Ever since Newton, we’ve known that ; and if , then — meaning a body will remain at rest or continue in uniform straight-line motion as long as the resultant force acting on it is zero. But if we want to move something — to start with, the steam engine’s crankshaft (Figure 5) — then we have to put some force into it. The logic works in reverse as well: if something is moving, forces will inevitably arise. Those forces are proportional to mass, and mass is proportional to volume. And a bigger machine is cheaper per unit of output.

If we increase the size of the steam engine, it can deliver more power — but the rotational speed has to be reduced, because the inertial and the so-called ‘fictitious’ forces that arise during motion become very real forces, which would exceed the strength limits of the structural materials available at the time. We could say: no problem, we’ll just build suitable gear reductions — a big gear on the steam engine’s crankshaft and a small gear on the generator shaft. That’s it. Almost.

We’ve solved the speed problem — but inside our reciprocating steam engine, large forces still arise, creating vibrations that become increasingly unmanageable, not only in the structural components, but even in the plant’s foundations around the engine.

Fine, let’s build a separate foundation — but countless pivot points with their many small parts are essentially a series of timed failure modes waiting to happen.

It runs smoothly and runs super fast – that’s cool

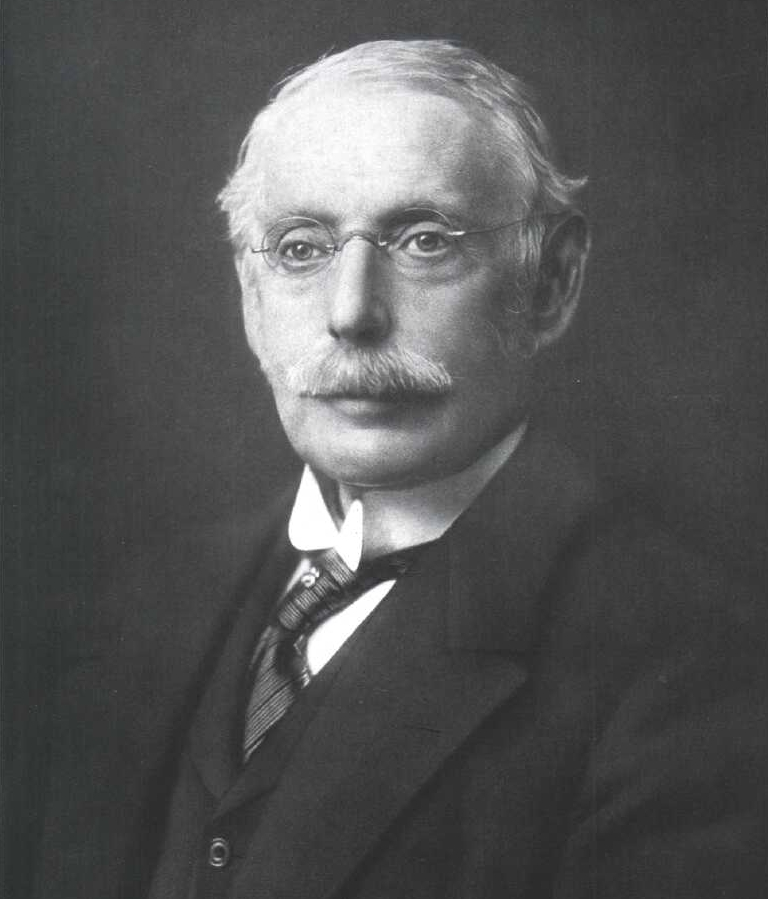

The solution was ultimately delivered by Charles Algernon Parsons, who—building on the work of Henri Victor Regnault—was the first to find an optimal design for a turbine rotating about its own axis. Parsons’ first turbine, in 1884, reached what was an astonishing 18,000 rpm at the time—while producing only minimal vibration. And at such a high rotational speed, the required synchronous speed can be achieved even with a relatively simple generator…

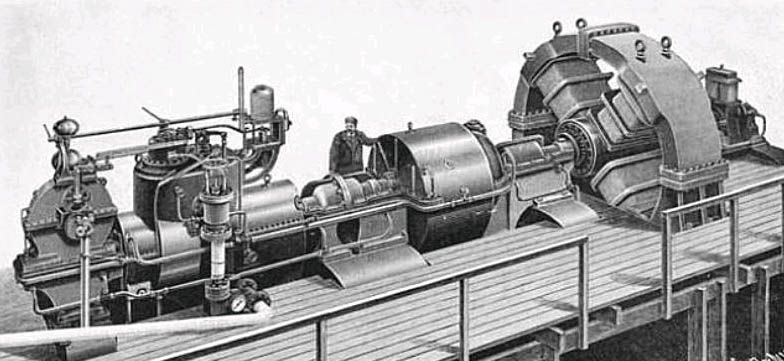

With Parsons’ steam turbine, all the problems of reciprocating steam engines were effectively solved, so by the early 1900s, the most fundamental structural elements characteristic of today’s coal-fired power plants were already in place. Massive boiler drums were fabricated by riveting, and the steam was then routed to the turbine. In the turbine, the steam expanded and drove the turbine shaft — and with it, the generator (Figure 6). The exhaust steam was then sent to the condenser, where it condensed, and the condensate water was fed back to the boiler — thus completing the Rankine cycle.

In the next part, we’ll take a thorough look at the steam-turbine cycle and the possible ways to increase efficiency. Don’t worry — there’s no need to be afraid of thermodynamics; there are few subjects in the world more logical than this one. Maybe statics 🙂